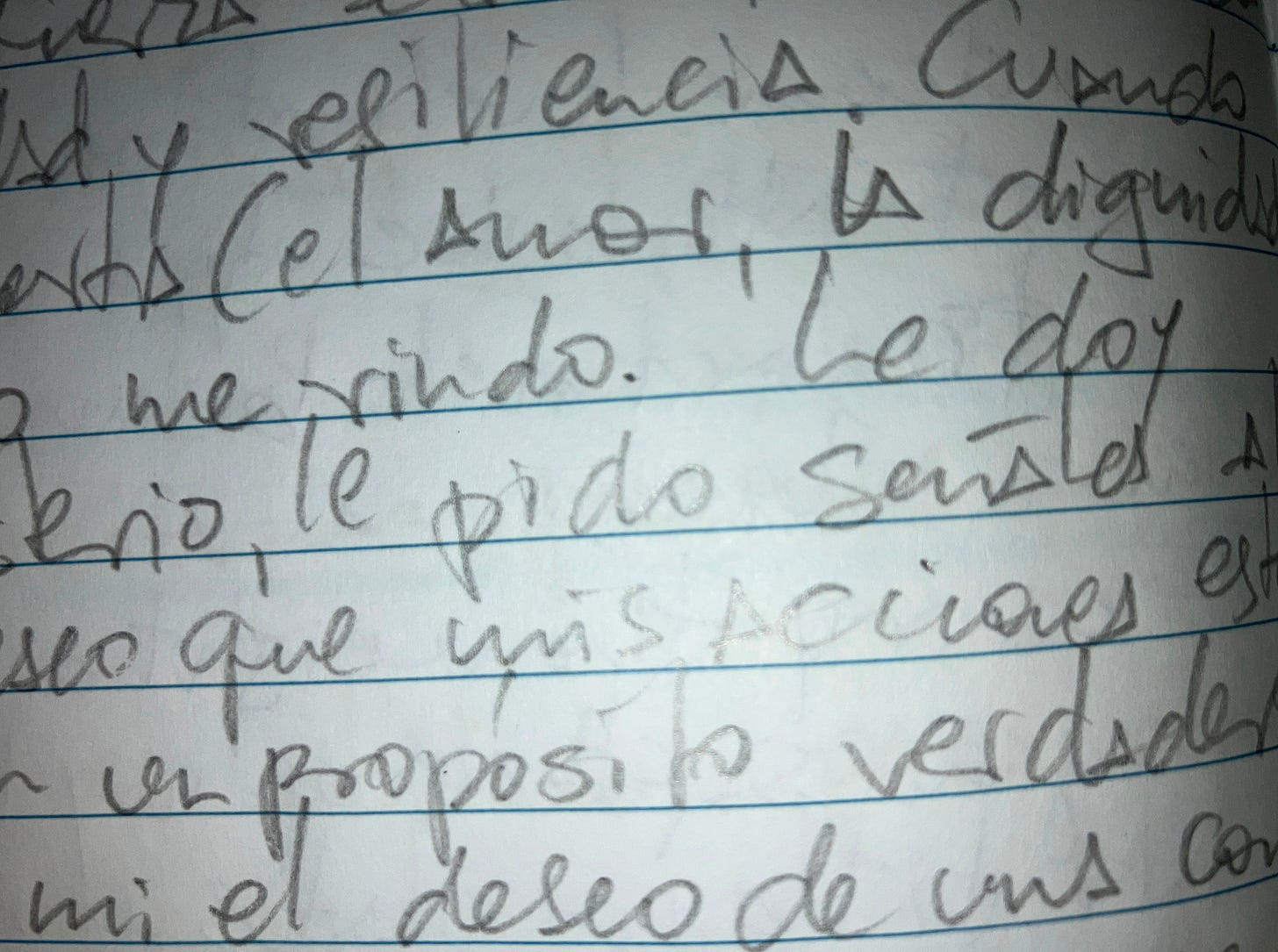

When I was nine, my teacher summoned my mother to school. I was the “good girl,” the model student — so I couldn’t imagine what I’d done wrong. My mother returned confused. The teacher had complained that she couldn’t read what I wrote because I didn’t press the pencil hard enough against the paper. My handwriting was “too clear,” too faint — almost invisible. That moment left a lasting mark. It introduced a strange kind of shame: not for making mistakes, but for not being loud enough on the page. For years, I carried that fear of not being seen or understood, even when trying to do everything right.

Decades later, something unexpected happened. A friend’s mother, also a teacher, mentioned my name. Another teacher overheard and somehow found me on Facebook. “I’m your teacher Martha,” she wrote. “Do you remember me?” I was surprised. How could she remember me, a quiet child whose only offense was writing too lightly? I replied kindly, “Yes, I remember you. You were the only teacher who ever called my parents to complain about me, because my writing was too faint to read. How could I forget?” And I said to myself, “If she appeared again in my life, maybe it’s time to forgive her, and finally free myself from that moment.”

Let's talk about handwriting. I’ve always been fascinated by left-handed people, perhaps because they seem to defy writing conventions just by being themselves. There’s something quietly subversive about the way they twist their hands or slant their words across the page. That subtle rebellion, that resistance to fit into pre-drawn lines, reminds me of how Sara Mesa writes.

Sara Mesa, a celebrated Spanish author known for her sharp and concise writing style. She was born January 1, 1976, in Madrid. She has published eight works of fiction, including Scar (winner of the Ojo Crítico Prize), Four by Four (a finalist for the Herralde Prize), An Invisible Fire (winner of the Premio Málaga de Novela), and Cara de Pan, which is forthcoming from Open Letter. Her books have been translated into more than ten languages and have earned widespread critical acclaim for their intense, atmospheric narratives that often explore power, isolation, and the complexities of human relationships.

This is the one related to my life: Mala letra (Bad Handwriting) 2016 by Sara Mesa.

The author of this book is unable to properly hold a pencil, despite the efforts her various teachers have made to correct this bad habit. Can someone write with good handwriting using a crooked pencil? This is one of the questions that hovers over this collection of ten stories: that of unruly, free, and accelerated writing—the kind of writing that scratches and tears at memory, that destroys memories and transforms them into something else.1

The ten short stories in the collection Mala letra explore childhood trauma, shame, rebellion, and the hidden darkness beneath ordinary lives. Whether it’s the silenced dread in La lechuza or the absurd confusion of Mármol, Mesa’s work pulses with emotional fractures. Children and women often occupy the margins—resisting obedience, aching for freedom, and carrying the burden of unspeakable pasts. These moments—when “something breaks, and everything changes”—are the heart of Mala letra.

Children who resist obedience and experience the difficult process of growing up with astonishment and loneliness; rebellious girls whose rebellion is underground, furious, and hardly useful; beings tormented—or not—by remorse and doubts; oxpeckers and otters that symbolize aggression or comfort; the confusion of seemingly normal lives that sometimes hide crimes and at other times only the desire to commit them.2

In today’s world, where handwriting is often replaced by typing and autocorrect, the subtle power of the written word—the way it carries emotion, identity, and memory—is at risk of being lost. Mala letra by Sara Mesa is a profound reminder of that. The very title evokes the vulnerability of expression, the way something as simple as handwriting can reveal deep truths about a person’s inner life and struggles.

Her characters often clash with voices that are ignored or dismissed, whether by family, teachers, or society at large. Like my own story with faint handwriting, Mesa’s stories reveal how small moments of misunderstanding or judgment can leave lasting emotional scars. In Mala letra, these wounds are not only personal but also social, highlighting how power, oppression, and silence shape the lives of those on the margins.

This is what makes Sara Mesa's work resonate beyond Spain: it echoes the wounds of many societies where silence, shame, and patriarchy rule beneath the surface.

For instance, the two standout stories mentioned above from Mala letra—La lechuza and Mármol—Sara Mesa masterfully examine how silence and shame shape young lives. In La lechuza, a seemingly quiet mother’s traumatic past lingers in the air, haunting the emotional atmosphere of her home. Through gestures and silence, her pain filters down to her daughter, who is left to navigate complex emotions without guidance.

Mesa resists melodrama; instead, she lets the weight of silence speak for itself. In Mármol, a group of schoolchildren confront a surreal classroom ritual that gradually veers into the absurd, revealing how systems of power and punishment are internalized from an early age. With no explanations from the adults, the children are left to make sense of their reality alone—navigating it with confusion, fear, and reluctant complicity. In both stories, what is left unsaid becomes the most powerful force of all.

Like the faint pencil lines of my childhood notebooks, Mesa’s characters live in the blurred space between what is seen and what is suppressed. Her stories suggest that language — and even writing — becomes a tool not just of expression, but of survival.

This is why I chose to compare her with Mexican author Ángeles Mastretta and renowned Mexican film directors — not only because I love them all, but their works share a similar courage in exposing the rawness beneath the surface of everyday life.

Sara Mesa’s work can be meaningfully compared with the intimate, evocative storytelling of “The Three Amigos” of Mexican cinema: Alfonso Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro, and Alejandro González Iñárritu:

Both Mesa and these directors tell intimate stories often centered on childhood, exploring themes of vulnerability and emotional complexity.

They focus on women and children living on the margins—for example, Cuarón’s Roma centers on a silenced woman navigating social hierarchies, while del Toro’s El espinazo del diablo (The Devil’s Backbone) explores childhood dread in a haunted orphanage.

Their narratives are often suggestive, reflecting emotional fragmentation and uncertainty, similar to Iñárritu’s nonlinear storytelling style (Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths).3

Sara Mesa and these Mexican filmmakers reveal how private pain is shaped and often compounded by larger, historical violence.

In her interview titled “Far-Reaching Minimalism” with María Ayete Gil, Mesa discusses her focus on partial, obscure, or ambiguous realities and how childhood perspectives offer unique insights into the world. Additionally, in her essay “Silencio administrativo,” she examines the impact of bureaucracy on the impoverished, highlighting systemic issues that hinder genuine healing in society.4

One Ángeles Mastretta novel that closely connects to these themes is Arráncame la vida (Tear This Heart Out). In this book, Mastretta tells the story of Catalina, a young woman growing up in post-revolutionary Mexico, navigating the complex dynamics of power, gender, and personal freedom. Catalina’s journey reflects the tension between societal expectations and the struggle to find one’s voice—a theme that echoes Sara Mesa’s focus on women who are often silenced or misunderstood within their families and communities. Like Mesa’s characters, Catalina’s story is about reclaiming identity and agency despite oppressive circumstances.5

On the cinematic side, Guillermo del Toro’s El espinazo del diablo offers a haunting exploration of childhood and education under extreme conditions. Set during the Spanish Civil War in a remote orphanage, the film examines how trauma, fear, and secrets shape the lives and perceptions of children. The orphanage itself is a place of both learning and isolation, where authority figures can be both protectors and oppressors. 6 This setting resonates with the atmosphere Sara Mesa creates in Mala letra, where education and childhood are tinged with confusion, fear, and the endeavor to be heard.

Like Sara Mesa, both Ángeles Mastretta and Guillermo del Toro reveal that education and growth are not just about acquiring knowledge—they’re about navigating emotional and social terrain, often in defiance of systems that silence or erase individual voices. Whether through fiction or film, these creators show how personal identity is shaped not only by what is taught, but by what must be unlearned.

Reflecting on my own experience—being “misread” for my handwriting, for expressing myself too lightly—Mala letra resonates on a deeply personal level. It reminds us how our forms of expression, whether written, spoken, or suppressed, are essential to how we understand ourselves and connect with others. Mesa’s stories echo Mastretta’s celebration of women finding their voice and del Toro’s haunting portraits of childhood caught in oppressive worlds. Across cultures and media, the longing to be seen, heard, and understood is a universal struggle.

By the end of Mala letra, we are not handed conclusions, but offered a quiet invitation: to pay attention to what remains unspoken, to reexamine the seemingly ordinary, and to ask how silence is passed down—or broken. Mesa shows us that writing, no matter how indocile or imperfect, can be an act of resistance. In doing so, she gives voice to what society so often tries to forget.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/28787165-mala-letra

Sara Mesa, Mala letra, Editorial Anagrama, 2016. Book description. https://www.anagrama-ed.es/libro/narrativas-hispanicas/mala-letra/9788433998057/NH_558?

Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths: A renowned Mexican journalist and documentary filmmaker returns home and works through an existential crisis as he grapples with his identity, familial relationships, and the folly of his memories.

https://www.ranker.com/list/the-best-alejandro-gonz%C3%A1lez-i%C3%B1%C3%A1rritu-movies/jason-bancroft

https://worldliteraturetoday.org/blog/interviews/far-reaching-minimalism-conversation-sara-mesa-maria-ayete-gil

https://kosmopolis.cccb.org/en/participants/mesa-sara/

Mala letra, which was published in 2016, contains the following stories (among others):

La lechuza

Palabras de piedra

Nada nuevo

Mármol

White People

Modelos animales

https://letrasmundo.com/explorando-la-profundidad-de-arrancame-la-vida-analisis-literario-de-angeles-mastretta/

https://www.fandango.com/people/guillermo-del-toro-165725

https://filmlifestyle.com/best-alfonso-cuaron-movies/